Retrieval Augmented Generation, or RAG, is, as of December 2023, probably the hottest topic around GenAI. In fact, along with David O’Dell, we recorded a couple of videos talking about RAG, its purpose and its components. At the heart of RAG is an Information Store, which can be queried to retrieve the relevant information, which is then passed to an LLM as context to help answer the initial question or query. The topic of this post is to dive into that Information Store.

For anybody reading blogs or watching videos on RAG, including mine, 99% of the time, the Information Store is a vector database, but vector databases are not the only options for RAG. The other popular option is a graph database and we are also seeing the emergence of graph database with vector indexing, trying to combine the best of both of these. The goal of this blog is to dive into vector and graph databases, look at the differences and why would one choose one over the other.

Vector Databases

History

Even though the popularity of vector databases has significantly increased in recent months with the increase in popularity of RAG, vector databases are not new. The emergence of vector databases seems to be linked to the effort to sequence DNA in the 1970s. Those sequencing efforts required a whole new paradigm to store the sequenced data in a whole new format as the data was represented as vectors, hence were vector databases born. By the 2000s, there are records showing vector databases being used at Stanford and at the National Institute for Health. Throughout the 2000s and 2010s, vector databases continued to grow in parallel with genetic research. Today, there is a plethora of options for anybody requiring a vector database. Here are some of the popular options:

- Pinecone

- Chroma

- Milvus

- Weaviate

What is a vector database?

A traditional database, be it relational or NoSQL, stores data of various types, such as string or numbers, whereas a vector database only stores vectors. In its simplest form, a vector is an array of numbers that can have 1 or multiple dimensions. Single or even dual dimensions vectors are fairly easy to manage, but when it comes to high-dimensional vectors, storing them is beneficial as it allows to optimize the search and retrieval of the vectors, through a family of algorithms called Approximate Nearest Neighbors. The purpose of this blog is not to dive into the various algorithms within that family, but, at a very high level, a vector database is queried by finding the most similar vector to the input vector using one of the Approximate Nearest Neighbor algorithms.

Vector databases are becoming popular in the field of GenAI, because algorithms are much better at analyzing and working with numbers versus strings, so being able to meaningfully represent text or images as vector unlocks a lot of potential capabilities.

Vectorizing data

As described above, vectors are the type of data stored in a vector database. This means that whatever data (text, image, etc…) we want to store, needs first to be encoded as a vector. This is called vectorization of the data. One of the most basic vectorization algorithm is called Bag of Words and below is an example of using it:

>>> from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import CountVectorizer

>>> vectorizer = CountVectorizer()

>>> text_to_vectorize = ['This is the text that I want to vectorize. It is a really interesting text']

>>> result = vectorizer.fit_transform(text_to_vectorize)

>>> result.toarray()

array([[1, 2, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1]])

>>> text_to_vectorize = ['A street fight breaks out between the Montagues and the Capulets, which is broken up by the ruler of Verona, Prince Escalus. He threatens the Montagues and Capulets with death if they fight again.']

>>> result = vectorizer.fit_transform(text_to_vectorize)

>>> result.toarray()

array([[1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 4, 1, 1,

1, 1, 1, 1]])In this example, the text This is a the text that I want to vectorize. It is a really interesting text ends up being represented by the vector [[1, 2, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1]] and the text A street fight breaks out between the Montagues and the Capulets, which is broken up by the ruler of Verona, Prince Escalus. He threatens the Montagues and Capulets with death if they fight again. from the Act 1 Scene 1 of Romeo and Juliet is represented by the vector [[1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 4, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1]]. As we can see the Bag of Words vectorizer is a very simple one, but provides a great illustration of how text can be represented as an array of numbers.

In the context of AI, GenAI and ML, the terms vectorization and embedding are used interchangeably, embedding is technically a subset of vectorization. Unlike vectorization, embedding attempts to capture the context and meaning of the text being vectorized, by leveraging specifically trained Large Language Models, such as BERT. HuggingFace offers a significant number of models that can be used to create embedding: https://huggingface.co/models?other=embedding, as does OpenAI: https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/embeddings

End to end data workflow

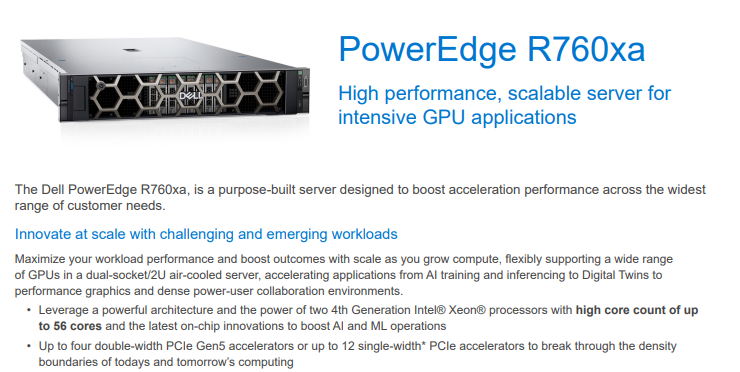

In this section, I will look at the entire workflow needed to add a document into a vector database and show how to query it. For this, I am going to use one of the most popular vector database: Chroma. Chroma is very easy to get started with and yet provide all the features I need for this blog, hence my choice. For the purpose of testing this workflow, my goal is to ingest the spec sheet for the Dell R760xa. I could have chosen the spec sheet for the XE9680, but I feel it is already getting so much press that it doesn’t need anymore, so instead I decided to make the R760xa the star of this blog. The spec sheet can be found here.

The first thing I’ll need to do is convert the pdf document. While there are lots of Python packages that can convert a PDF document into text, I have chosen to use tika as it is the one, that has given me the best results so far. Tika can be installed using pip install tika , but it will need java installed in order to work. Once Tika is installed, let’s convert the PowerEdge R760xa spec sheet PDF into text:

>>> import tika

>>> from tika import parser

>>> text = parser.from_file('/home/bertrand/poweredge-r760xa-spec-sheet.pdf')

2023-12-13 00:38:01,229 [MainThread ] [WARNI] Failed to see startup log message; retrying...

>>> print(text["content"])

PowerEdge R760xa

High performance, scalable server for

intensive GPU applications

The Dell PowerEdge R760xa, is a purpose-built server designed to boost acceleration performance across the widest

range of customer needs.

Innovate at scale with challenging and emerging workloads

Maximize your workload performance and boost outcomes with scale as you grow compute, flexibly supporting a wide range

of GPUs in a dual-socket/2U air-cooled server, accelerating applications from AI training and inferencing to Digital Twins to

performance graphics and dense power-user collaboration environments.

• Leverage a powerful architecture and the power of two 4th Generation Intel® Xeon® processors with high core count of up

to 56 cores and the latest on-chip innovations to boost AI and ML operations

• Up to four double-width PCIe Gen5 accelerators or up to 12 single-width* PCIe accelerators to break through the density

boundaries of todays and tomorrow’s computingHere is a screenshot of the top of the spec sheet:

While the formatting is lost, which is to be expected, the content of the file is properly reproduced by Tika.

While it is possible to vectorize an entire document as a single entity, it is usually advise to split the document into smaller sections called chunks. A chunk can be a single sentence, a paragraph or a specific number of characters. When chunking a document, it is also possible to specify how much the chunks should overlap one another.

Let’s now chunk the newly converted spec sheet. To do that, we will be leveraging langchain and its CharacterTextSplitter module.

>>> from langchain.text_splitter import CharacterTextSplitter

>>> text_splitter = CharacterTextSplitter(chunk_size=1000, chunk_overlap=200)

>>> chunks = text_splitter.create_documents([text["content"]])

>>> len(chunks)

11

>>> chunks[0]

Document(page_content='PowerEdge R760xa\nHigh performance, scalable server for \nintensive GPU applications\n\nThe Dell PowerEdge R760xa, is a purpose-built server designed to boost acceleration performance across the widest \nrange of customer needs.\n\nInnovate at scale with challenging and emerging workloads\nMaximize your workload performance and boost outcomes with scale as you grow compute, flexibly supporting a wide range \nof GPUs in a dual-socket/2U air-cooled server, accelerating applications from AI training and inferencing to Digital Twins to \nperformance graphics and dense power-user collaboration environments.\n\n• Leverage a powerful architecture and the power of two 4th Generation Intel® Xeon® processors with high core count of up \nto 56 cores and the latest on-chip innovations to boost AI and ML operations\n\n• Up to four double-width PCIe Gen5 accelerators or up to 12 single-width* PCIe accelerators to break through the density \nboundaries of todays and tomorrow’s computing')We can see that the chunking of the converted PDF resulted in 11 chunks. Obviously, the number of chunks will depend on the size of the chunk. We can also see that chunks[0] contains the beginning of the text. Prior to loading the embeddings into Chroma, I need to calculate the embeddings. For this, I am going to use Langchain again and its embeddings module. From that embeddings module, I will be using the HuggingFaceEmbeddings as it allows me to use any of the Hugging Face text embedding models:

>>> from langchain.embeddings import HuggingFaceEmbeddings

>>> embeddings_model = HuggingFaceEmbeddings(

... model_name='sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-l6-v2',

... model_kwargs={'device': 'cpu'},

... encode_kwargs={'normalize_embeddings': False}

... )

Before I can calculate the embeddings for the chunks, I need to convert the chunks, which are of type Document to text. To do this, I just need to create an array containing the page_content content from each chunk:

>>> chunks_text = [chunk.page_content for chunk in chunks]I can also verify that my embedding model works by feeding it the content of a single chunk:

>>> embeddings = embeddings_model.embed_query(chunks[0].page_content)And this is what the resulting embedding looks like:

>>> embeddings

[-0.02706354856491089, -0.008369384333491325, -0.06973616778850555, 0.07999780029058456, -0.03280850499868393, -0.026314767077565193, -0.06220933794975281, -0.006489351857453585, -0.08278238028287888, -0.02635814994573593, -0.041829101741313934, 0.012268655002117157, -0.03551347553730011, -0.013869951479136944, 0.013234278187155724, 0.09128635376691818, 0.050749100744724274, -0.01712208427488804, -0.04311386123299599, -0.028402598574757576, -0.02399730123579502, -0.0668458491563797, -0.02934863232076168, -0.04248754680156708, 0.04319565370678902, -0.010733521543443203, 0.03710585832595825, -0.00037649794830940664, -0.019825058057904243, 0.0007032508729025722,

...

0.09203413873910904, -0.029482049867510796, 0.02843594178557396, 0.013403371907770634, -0.0013101889053359628, 0.08709444105625153, 0.091305211186409, -0.05220574140548706, 0.05776556581258774, 0.038633327931165695, 0.042991604655981064, 0.03125453740358353, -0.07543152570724487, -0.020672105252742767, -0.062139324843883514]I basically now need to calculate such embeddings for all the chunks. For this, I just need to pass my newly created array chunks_text to the embedding model:

>>> embeddings = embeddings_model.embed_documents(chunks_text)

>>> len(embeddings)

11

>>> embeddings[0]

[-0.02706354670226574, -0.008369388058781624, -0.06973617523908615, 0.07999782264232635, -0.032808490097522736, -0.026314768940210342, -0.06220933422446251, -0.0064893499948084354, -0.08278239518404007, -0.026358148083090782, -0.041829098016023636, 0.012268641032278538, -0.03551347553730011, -0.013869939371943474, 0.013234292156994343, 0.09128635376691818, 0.05074910819530487, -0.01712210290133953, -0.043113868683576584, -0.028402581810951233, -0.02399730123579502, -0.0668458491563797, -0.029348626732826233, -0.042487528175115585,

...

0.09130518138408661, -0.05220572650432587, 0.05776553973555565, 0.0386333130300045, 0.04299161583185196, 0.031254544854164124, -0.07543151080608368, -0.020672108978033066, -0.06213933974504471]Now that we have chunked the text and created the embeddings for each chunk, let’s load the chunks into Chroma. Here again, I am going to leverage Langchain as it provides helper functions for a number of vector databases, including Chroma. The helper functions for Chroma actually allows us to calculate the embeddings as we load the vectors into the database:

>>> from langchain.vectorstores import Chroma

>>> chromadb = Chroma.from_documents(chunks, embeddings_model)

>>> query = "How many PCIe slots does the R760xa have"

>>> docs = chromadb.similarity_search(query)

>>> print(docs[0].page_content)

PowerEdge R760xa

High performance, scalable server for

intensive GPU applications

The Dell PowerEdge R760xa, is a purpose-built server designed to boost acceleration performance across the widest

range of customer needs.

Innovate at scale with challenging and emerging workloads

Maximize your workload performance and boost outcomes with scale as you grow compute, flexibly supporting a wide range

of GPUs in a dual-socket/2U air-cooled server, accelerating applications from AI training and inferencing to Digital Twins to

performance graphics and dense power-user collaboration environments.

• Leverage a powerful architecture and the power of two 4th Generation Intel® Xeon® processors with high core count of up

to 56 cores and the latest on-chip innovations to boost AI and ML operations

• Up to four double-width PCIe Gen5 accelerators or up to 12 single-width* PCIe accelerators to break through the density

boundaries of todays and tomorrow’s computingAs we can see, loading the chunks into the database was easy, thanks to the helper functions. Once the chunks are loaded, it is possible to query them. As I only have a single document in the database, the result is obvious, but still shows that it is possible to query the database and find vectors that are similar to the query provided.

Downsides of vector databases

In the previous example, the query I made is related to the topic of the document that I ingested into the vector database, but what happens if the query is not related to the topic, then what? Well, let’s try it:

>>> query = "Who is president of the united states"

>>> docs = chromadb.similarity_search(query)

>>> print(docs[0].page_content)

Cyber Resilient Architecture for Zero Trust IT environment & operations

Security is integrated into every phase of the PowerEdge lifecycle, including protected supply chain and factory-to-site integrity

assurance. Silicon-based root of trust anchors end-to-end boot resilience while Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) and role-based

access controls ensure trusted operations.

Increase efficiency and accelerate operations with autonomous collaboration

The Dell OpenManage™ systems management portfolio delivers a secure, efficient, and comprehensive solution for PowerEdge

servers. Simplify, automate and centralize one-to-many management with the OpenManage Enterprise console and iDRAC.

>>> query = "What is Italy"

>>> docs = chromadb.similarity_search(query)

>>> print(docs[0].page_content)

Search our

Resource Library

Follow PowerEdge

servers on Twitter

Learn more about our

PowerEdge servers]

Discover more about PowerEdge servers

Copyright © 2023 Dell Inc. or its subsidiaries. All Rights Reserved. Dell Technologies, Dell, and other trademarks are

trademarks of Dell Inc. or its subsidiaries. Other trademarks may be trademarks of their respective owners.

August 2023

https://www.delltechnologies.com/en-us/solutions/openmanage/index.htm

https://www.delltechnologies.com/en-us/contactus.htm

https://www.delltechnologies.com/en-us/search.htm#sort=relevancy&f:productFacet=[43609]

https://twitter.com/dellemcservers

https://www.dell.com/en-us/dt/services/index.htm?ref=poweredgespecsheet

Hang on a sec, the answer to the question What is Italy is found in the PowerEdge R760xa spec sheet? How is that possible? It is possible because all the vector database does is to calculate the embeddings/vector for the question What is Italy and then return whichever vector is the closest to vector of the question, whether that vector is actually related to the question or not. This is one of the major downsides of a vector database: it will always return an answer whether that answer is relevant to the question or not.

The other major downside of a vector database is that the information required to answer the query can be distributed across multiple chunks, leading to inefficiency in the retrieval process and potential data coherence.

Best Uses for vector databases

Because of their structure and the type of data they store, ie vectors, vector databases are typically best suited for use cases involving text and semantic searches, which is why they are so popular as the Information Store of choice in RAG application.

Graph databases

History

Now that I have shown what vector databases are and how they work, let’s talk about graph databases. Graph databases are a completely different animal from vector databases.

According to Wikipedia, the history of graph databases can be traced back to the 1960s, when emerged the concept of navigational databases, which supported a tree-like structure. Refinements were done throughout the 1960s, but it is truly in the 1990s, with emergence of commercial object databases, inside of which, it was possible to define objects, but more importantly, relationships, also known as graph, between objects. It is only in mid-2000s that modern graph databases, with ACID guarantees, came about. As with vector databases, there are lots of options to choose from, such as:

- Neo4j

- ArangoDB

- NebulaGraph

- Amazon Neptune

For the purpose of this blog, I will be using Neo4J. My choice relies on a number of reasons:

- Neo4J is the most popular graph database,

- Plenty of documentation available on Neo4J

- Neo4J is integrated into Langchain

Similarly to the section on vector database, for this section, I will also be using Langchain to ingest data into the graph database, so integration with it is critical.

What is a graph database

Unlike a traditional SQL database, which stores data in rows and columns, a graph database stores data in nodes, edges and properties.

A node represents an entity or an instance. For instance, a node could be an instance of a car, a dog, a network card, a server, etc… An edge between 2 nodes represents a relationship between those 2 nodes.

Figure 1 shows an example of relationship between 2 nodes: Node A is an instance of type Server with a value of R760xa while Node B is an instance of type Network Card with a value of Intel X710-T4L and the relationship between the 2 is “installed_in”. Node B can also have a numbers of properties, such as description, part number, size, speed, price, etc… Similarly, Node A can have the following as properties: service tag, # of PCI slots, CPU Info, memory info, etc…

Because of their unique data types, graph databases require a specific language to perform CRUD operations and to run queries. The most popular language for graph databases is called Cypher and is supported by most graph databases. In this blog, I will be using Cypher to show how it can be used to perform basic operations.

Inserting data into a graph database

Inserting data into a graph database is fairly simple, as I am going to show, but unlike a vector database, taking a PDF document and inserting it into the database is significantly more complex, so let’s break things down a little bit.

First of all, let’s show how to natively insert data into a graph database. To interact with the database, I will be using the langchain.graphs module, which rely on the neo4j Python module. It is possible to only use the neo4j Python module, but as I will be using langchain later in the blog, I have decided to leverage the langchain module.

Let’s insert sample data based on Figure 1:

>>> from langchain.graphs import Neo4jGraph

>>> graph = Neo4jGraph(url="bolt://localhost:7687", username="neo4j", password="password")

>>> graph.query(

... """

... MERGE(s:Server {name:"R760xa"})

... WITH s

... UNWIND ["Intel X710-T4L", "Intel X710-T2L", "Mellanox ConnectX-6", "Mellanox ConnectX-7"] AS network_card

... MERGE(n: Network_Card {name: network_card})

... MERGE (n)-[:AVAILABLE_FOR]->(s)

... """

... )

[]

>>> graph.refresh_schema()

>>> print(graph.schema)

Node properties are the following:

Server {name: STRING},Network_Card {name: STRING}

Relationship properties are the following:

The relationships are the following:

(:Network_Card)-[:AVAILABLE_FOR]->(:Server)As per Figure 1, I have 2 node types: Server and Network_Card and the relationship between those 2 node types is AVAILABLE_FOR. In example above, the AVAILABLE_FOR relationship means that network card Intel X710-T4L is available for a server R760xa.

When I connect to the Neo4j database directly and display the inserted data, it shows the following picture:

We can see the 4 instance of node type Network_Card, the single instance of node type Server and their relationships. Now, I can run queries against that data. For instance, if I want to return all the network cards available for the R760xa server, I can run:

>>> graph.query(

... """

... MATCH (nc:Network_Card)-[:AVAILABLE_IN]->(s:Server {name: "R760xa"})

... RETURN nc

... """

... )

[{'nc': {'name': 'Intel X710-T4L'}}, {'nc': {'name': 'Intel X710-T2L'}}, {'nc': {'name': 'Mellanox ConnectX-7'}}, {'nc': {'name': 'Mellanox ConnectX-6'}}]The query above was written in Cypher, executed against the database and return the expected results. The problem though is who is going to want to execute Cypher queries? Certainly not me. The same way as in a vector database, I want to be able to ask a question, get an answer and have something do the translation from my question to a Cypher queries in the process. This is where Langchain comes to the rescue as Langchain offers a chain to translate a question into a Cypher query: GraphCypherQAChain, so let’s try it:

>>> from langchain.chains import GraphCypherQAChain

>>> from langchain.chat_models import ChatOpenAI

>>> chain = GraphCypherQAChain.from_llm(

... ChatOpenAI(temperature=0, model_name="gpt-4"), graph=graph, verbose=True

... )The GraphCypherQAChain leverages an LLM to perform the translation from question to Cypher. In this example, I am using the GPT-4 from OpenAI, through the ChatOpenAI module. As with everything OpenAI, you will need an OpenAI API key in order for this to work.

Now that I have defined the chain, let’s use it to ask questions to the database:

>>> chain.run("Which network cards are available in the R760xa server?")

> Entering new GraphCypherQAChain chain...

Generated Cypher:

MATCH (n:Network_Card)-[:AVAILABLE_IN]->(s:Server {name: 'R760xa'}) RETURN n.name

Full Context:

[{'n.name': 'Intel X710-T4L'}, {'n.name': 'Intel X710-T2L'}, {'n.name': 'Mellanox ConnectX-7'}, {'n.name': 'Mellanox ConnectX-6'}]

> Finished chain.

'The network cards available in the R760xa server are Intel X710-T4L, Intel X710-T2L, Mellanox ConnectX-7, and Mellanox ConnectX-6.'Success!!! I have managed to ask a question in English and got the right answer.

While extremely simple, the example above showcases the complexity of working with graph database, ie the need to have an LLM translating between human language and Cypher. This translation doesn’t solely apply when querying the database, it also applies when ingesting data. During the data ingest phase, I need the LLM to identify the types of nodes and their associated relationships defined in the document I am looking to ingest. Unfortunately, this will depend on the type of data that I am ingesting. If I am ingesting data related to servers and their specs, then I need to extract nodes representing various components, use cases, warranty, and features, whereas, for data related to the spec sheet of a storage array, it will be about capacity, drives, snapshots and expansion. Both are spec sheets, but because of the type of product they relate to, the nodes and relationships will be vastly different. there lies the difficulty with graph database: it all depends on how the document gets parsed and how nodes, relationships and properties are extracted.

So how do I get an LLM to recognize the right types of node and their associated relationships? Unfortunately, there is no simple answer to that question. Unlike vectorizing chunks of text which is a deterministic process, extracting nodes, relationships and properties falls squarely in the it depends realm, meaning that the LLM will need to be guided instructed on what to do, through prompt engineering.

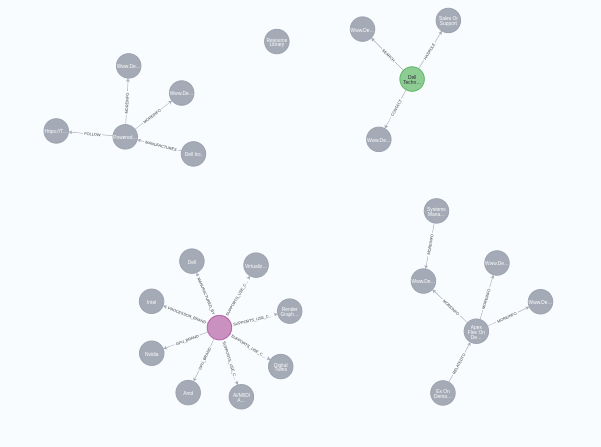

In researching this blog, I have found that information on how to do this is pretty limited. Thankfully, I found this blog by Tomaz Bratanic, where he goes through the process of taking a text document and ingesting it into a graph database. I have taken Tomaz’s code and adapted it for my purpose and this is the result I got when ingesting the R760xa PDF spec sheet:

It found 25 nodes in total and built 20 relationships between various nodes. Here is the code on how to do that:

import tika

from tika import parser

from langchain.graphs import Neo4jGraph

from langchain.graphs.graph_document import (

Node as BaseNode,

Relationship as BaseRelationship,

GraphDocument,

)

from langchain.schema import Document

from typing import List, Dict, Any, Optional

from langchain.pydantic_v1 import Field, BaseModel

from langchain.chains.openai_functions import (

create_openai_fn_chain,

create_structured_output_chain,

)

from langchain.chat_models import ChatOpenAI

from langchain.prompts import ChatPromptTemplate

from langchain.text_splitter import TokenTextSplitter

from tqdm import tqdm

class Property(BaseModel):

"""A single property consisting of key and value"""

key: str = Field(..., description="key")

value: str = Field(..., description="value")

class Node(BaseNode):

properties: Optional[List[Property]] = Field(None, description="List of node properties")

class Relationship(BaseRelationship):

properties: Optional[List[Property]] = Field(None, description="List of relationship properties")

class KnowledgeGraph(BaseModel):

"""Generate a knowledge graph with entities and relationships."""

nodes: List[Node] = Field(..., description="List of nodes in the knowledge graph")

rels: List[Relationship] = Field(..., description="List of relationships in the knowledge graph")

def format_property_key(s: str) -> str:

words = s.split()

if not words:

return s

first_word = words[0].lower()

capitalized_words = [word.capitalize() for word in words[1:]]

return "".join([first_word] + capitalized_words)

def props_to_dict(props) -> dict:

"""Convert properties to a dictionary."""

properties = {}

if not props:

return properties

for p in props:

properties[format_property_key(p.key)] = p.value

return properties

def map_to_base_node(node: Node) -> BaseNode:

"""Map the KnowledgeGraph Node to a base Node."""

properties = props_to_dict(node.properties) if node.properties else {}

properties["name"] = node.id.title()

return BaseNode(id=node.id.title(), type=node.type.capitalize(), propertes=properties)

def map_to_base_relationship(rel: Relationship) -> BaseRelationship:

"""Map the KnowledgeGraph Relationship to the base Relationship."""

source = map_to_base_node(rel.source)

target = map_to_base_node(rel.target)

properties = props_to_dict(rel.properties) if rel.properties else {}

return BaseRelationship(source=source, target=target, type=rel.type, properties=properties)

def get_extraction_chain(allowed_nodes: Optional[List[str]] = None, allowed_rels: Optional[List[str]] = None):

prompt = ChatPromptTemplate.from_messages(

[(

"system",

f"""# Knowledge Graph Instructions for GPT-4

## 1. Overview

You are a top-tier algorithm designed for extracting information in structured formats to build a knowledge graph.

- **Nodes** represent entities and concepts. They're akin to Wikipedia nodes.

- The aim is to achieve simplicity and clarity in the knowledge graph, making it accessible for a vast audience.

## 2. Labeling Nodes

- **Consistency**: Ensure you use basic or elementary types for node labels.

- For example, when you identify an entity representing a person, always label it as **"person"**. Avoid using more specific terms like "mathematician" or "scientist".

- **Node IDs**: Never utilize integers as node IDs. Node IDs should be names or human-readable identifiers found in the text.

{'- **Allowed Node Labels:**' + ", ".join(allowed_nodes) if allowed_nodes else ""}

{'- **Allowed Relationship Types**:' + ", ".join(allowed_rels) if allowed_rels else ""}

## 3. Handling Numerical Data and Dates

- Numerical data, like age or other related information, should be incorporated as attributes or properties of the respective nodes.

- **No Separate Nodes for Dates/Numbers**: Do not create separate nodes for dates or numerical values. Always attach them as attributes or properties of nodes.

- **Property Format**: Properties must be in a key-value format.

- **Quotation Marks**: Never use escaped single or double quotes within property values.

- **Naming Convention**: Use camelCase for property keys, e.g., `birthDate`.

## 4. Coreference Resolution

- **Maintain Entity Consistency**: When extracting entities, it's vital to ensure consistency.

If an entity, such as "John Doe", is mentioned multiple times in the text but is referred to by different names or pronouns (e.g., "Joe", "he"),

always use the most complete identifier for that entity throughout the knowledge graph. In this example, use "John Doe" as the entity ID.

Remember, the knowledge graph should be coherent and easily understandable, so maintaining consistency in entity references is crucial.

## 5. Strict Compliance

Adhere to the rules strictly. Non-compliance will result in termination.

"""),

("human", "Use the given format to extract information from the following input: {input}"),

("human", "Tip: Make sure to answer in the correct format"),

])

return create_structured_output_chain(KnowledgeGraph, llm, prompt, verbose=False)

def extract_and_store_graph(document: Document, nodes: Optional[List[str]] = None, rels: Optional[List[str]] = None) -> None:

extract_chain = get_extraction_chain(nodes, rels)

data = extract_chain.run(document.page_content)

graph_document = GraphDocument(

nodes = [map_to_base_node(node) for node in data.nodes],

relationships = [map_to_base_relationship(rel) for rel in data.rels],

source = document

)

graph.add_graph_documents([graph_document])

url = "bolt://192.168.122.200:7687"

username = "neo4j"

password = "password"

openai_api_key = <ENTER YOUR OPENAI API KEY HERE>

llm = ChatOpenAI(model="gpt-3.5-turbo-16k", temperature=0, openai_api_key=openai_api_key)

graph = Neo4jGraph(url=url, username=username, password=password)

text = parser.from_file('/home/bertrand/poweredge-r760xa-spec-sheet.pdf')

text_splitter = TokenTextSplitter(chunk_size=2000, chunk_overlap=24)

documents = text_splitter.create_documents([text["content"]])

for i, d in tqdm(enumerate(documents), total=len(documents)):

extract_and_store_graph(d)

As you can see, compared to vectorizing chunks of text which can be done in a few lines of code, it is definitely more complex, but then I can also ask questions:

>>> from langchain.chains import GraphCypherQAChain

>>> from langchain.graphs import Neo4jGraph

>>> graph = Neo4jGraph(url="bolt://192.168.122.200:7687", username="neo4j", password="password")

>>> graph.refresh_schema()

>>> from langchain.chat_models import ChatOpenAI

>>> cypher_chain = GraphCypherQAChain.from_llm(

... graph=graph,

... cypher_llm=ChatOpenAI(temperature=0, model="gpt-4", openai_api_key=openai_api_key),

... qa_llm=ChatOpenAI(temperature=0, model="gpt-4", openai_api_key=openai_api_key),

... validate_cypher=True,

... verbose=True

... )

>>> cypher_chain.run("What use case are supported by the Poweredge R760Xa?")

> Entering new GraphCypherQAChain chain...

Generated Cypher:

MATCH (s:Server {id: "Poweredge R760Xa"})-[:SUPPORTS_USE_CASE]->(u:Use_case) RETURN u.id

Full Context:

[{'u.id': 'Ai/Ml/Dl Training And Inferencing'}, {'u.id': 'Digital Twins'}, {'u.id': 'Render Graphics'}, {'u.id': 'Virtualization And Vdi Graphics'}]

> Finished chain.

'The Poweredge R760Xa supports various use cases including AI/ML/DL Training and Inferencing, Digital Twins, Render Graphics, and Virtualization and VDI Graphics.'By comparison, the same question asked to the vector databases returned the following answer:

>>> query = "What the use cases are supported by the PowerEdge R760xa?"

>>> docs = chromadb.similarity_search(query)

>>> docs

[Document(page_content='Sustainability\nFrom recycled materials in our products and packaging, to thoughtful, innovative options for energy efficiency, the PowerEdge \nportfolio is designed to make, deliver, and recycle products to help reduce the carbon footprint and lower your operation costs. \nWe even make it easy to retire legacy systems responsibly with Dell Technologies Services.\n\nRest easier with Dell Technologies Services\nMaximize your PowerEdge Servers with comprehensive services ranging from \nConsulting, to ProDeploy and ProSupport suites, Data Migration and more \n– available across 170 countries and backed by our 60K+ employees and \npartners.\n\n* Indicates up to 12 Single-width (PCIe x8), and up to 8 Single-width (PCIe x16).\n** Future releases will include additional features.\n\nSpecification Sheet\n\nPowerEdge R760xa\nThe Dell PowerEdge R760xa is a high-\nperformance scale -as you grow server \ndesigned for use cases like'), Document(page_content='PowerEdge R760xa\nHigh performance, scalable server for \nintensive GPU applications\n\nThe Dell PowerEdge R760xa, is a purpose-built server designed to boost acceleration performance across the widest \nrange of customer needs.\n\nInnovate at scale with challenging and emerging workloads\nMaximize your workload performance and boost outcomes with scale as you grow compute, flexibly supporting a wide range \nof GPUs in a dual-socket/2U air-cooled server, accelerating applications from AI training and inferencing to Digital Twins to \nperformance graphics and dense power-user collaboration environments.\n\n• Leverage a powerful architecture and the power of two 4th Generation Intel® Xeon® processors with high core count of up \nto 56 cores and the latest on-chip innovations to boost AI and ML operations\n\n• Up to four double-width PCIe Gen5 accelerators or up to 12 single-width* PCIe accelerators to break through the density \nboundaries of todays and tomorrow’s computing'), Document(page_content='Specification Sheet\n\nPowerEdge R760xa\nThe Dell PowerEdge R760xa is a high-\nperformance scale -as you grow server \ndesigned for use cases like\n\n• AI/ML/DL Training and Inferencing \n• Digital Twins, render graphics\n• Virtualization and VDI graphics\n\nhttps://www.dell.com/en-us/dt/services/consulting-services/index.htm#tab0%3D0&tab0=0\nhttps://www.dell.com/en-us/dt/services/deployment-services/prodeploy-enterprise-suite.htm#tab0=0\nhttps://www.dell.com/en-us/dt/services/support-services/index.htm\nhttps://www.dell.com/en-us/dt/services/data-migration.htm\n\n\nFeature Technical Specifications\nProcessor Up to two 4th Generation Intel Xeon Scalable processor with up to 56 cores per processor and optional Intel® QuickAssist \n\nTechnology\nMemory • 32 DDR5 DIMM slot, supports RDIMM 8 TB max, speeds up to 4800 MT/s\n\n• Supports registered ECC DDR5 DIMMs only\nStorage controllers • Internal controllers: PERC H965i, PERC H755, PERC H755N, PERC H355, HBA355i'), Document(page_content='visit Dell.com -> Solutions -> OEM Solutions..\n\nAPEX on Demand\nAPEX Flex on Demand Acquire the technology you need to support your changing business with \npayments that scale to match actual usage. For more information, visit \nwww.delltechnologies.com/en-us/payment-solutions/flexible-consumption/flex-on-demand.htm.\n\nhttps://www.dell.com/support/contents/en-us/article/Product-Support/Self-support-Knowledgebase/enterprise-resource-center/server-operating-system-support\nhttps://www.dell.com/en-us\nhttp://www.delltechnologies.com/en-us/payment-solutions/flexible-consumption/flex-on-demand.htm\n\n\nLearn more about our \nsystems management \n\nsolutions\n\nContact a Dell \nTechnologies Expert \nfor Sales or Support\n\nSearch our \nResource Library\n\nFollow PowerEdge \nservers on Twitter\n\nLearn more about our \nPowerEdge servers]\n\nDiscover more about PowerEdge servers')]I have highlighted code is the correct answer and we can see that it is actually, the 3rd chunk returned by the similarity search. The 1st returned chunk includes the terms use case but doesn’t actually contain the use cases.

Unlike vector database, if the information requested isn’t in the graph database, it doesn’t return anything:

>>> cypher_chain.run("Who is the president of the United States?")

> Entering new GraphCypherQAChain chain...

Generated Cypher:

MATCH (p:Person)-[:HASROLE]->(r:Role) WHERE r.id = "President" AND p.Company.id = "United States" RETURN p.id

Full Context:

[]

> Finished chain.

"I'm sorry, but I don't know the answer."Downsides of Graph Databases

The complexity of ingesting data into a graph database is probably the major downside. The challenge presented by that complexity is compounded by results varying significantly depending on the values of various parameters, such as chunk size or LLM. For instance, using the exact same chunk size, but switching to GPT-4 instead of GPT-3.5 Turbo, creates the following results:

GPT-4 found only 5 nodes and 3 relationships, compared to 25 and 20 respectively for GPT-3.5 Turbo. Everything else was the exact same. Similarly, if I change the chunk size to 1000 instead of 2000, but keep the same LLM, I get vastly different results:

This time, the LLM found 87 nodes and 84 relationships. As I have said, vastly different results.

The final downside of graph database is their performance with complex queries over large graphs. While there is very little research done on the performance comparison between graph and vector databases in the context of RAG, this whitepaper has shown the challenges of graph database compared to traditional SQL database.

Best use cases for graph databases

Because of the way graph databases store data, they are well suited for systems exploring the relationships between entities. Graph databases also allow multi-hop queries, ie queries leveraging multiple relationships between multiple entities. This make them particularly well suited to be the Information Store in RAG, as they allow much more complex queries than vector database.

Final Thoughts

In the context of RAG, both vector and graph databases are an excellent choice to act as the Information Store. Thanks to their simplicity, vector databases provide a faster time to market, at the expense of being able to answer complex queries. On the other hand, graph databases have a much steeper learning curve and implementation complexities, but offer a much richer set of queries.

So which one is the best? The answer to that question is my favourite one: it depends. It depends on a multitude of factors, such as the use case, the data itself, etc…, but while there is a lot of ink being spent on vector databases in the context of RAG, I think that graph databases should also get a serious look for the value they provide within such system.

Because of the length of this blog, I have decided to record a couple of videos showing only the demo part of the blog. I recorded one video for the vector database (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=it84XR6N4hk) and one video for the graph database (https://youtu.be/degdHwCUtF0). Both of these show how to ingest a PDF file into their respective databases.

Leave a reply to How to Ingest a PDF File into a Vector Database – GEOS Cancel reply